An interview with Suyin Looui, Sons & Daughters

One woman's five year journey to document Chinese-Canadian cafés, accompanied by her dad

I used to interview people. A lot.

Over three years I interviewed one hundred diaspora about their relationship to Chinese food and identity, eventually commissioning 41 artists to bring their stories to life in this exhibition. My short lived cabbage chronicle Asian Slaw Alliance was curtailed by work on my book, in which I interviewed at least 30 subjects.

I’ve been chomping at the bit to get back to what I love doing: sharing other people’s good work. Today I hope you’ll be as touched as I was about:

Sons & Daughters

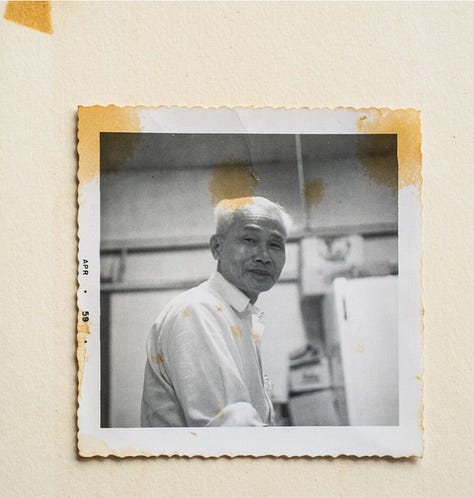

For five years, London-based director Suyin Looui travelled across Canada with her father, Steffan, to document Chinese-Canadian cafés. At the heart of her journey was a visit back to her grandfather’s small-town Chinese restaurant, which remains on Oxbow’s Main Street over 60 years later.

Wherever Chinese immigrants have historically landed, they have brought, evolved and marketed their food, based on a combination of taste memory, homesickness and economics. The edible legacy of such movement is the body of cafés that define every Canadian town, from Sechelt, British Columbia to Truro, Nova Scotia.1 It’s worth slowly taking this journey with Suyin and Steffan on her website to understand the literal breadth — as well as personal depth — of their undertaking.

Read on below for my Q&A with Suyin, and do vote for them in the Webby Awards ‘Cultural Website’ category before 17th April!

You must have eaten a lot of food on your trip! What were some memorable meals?

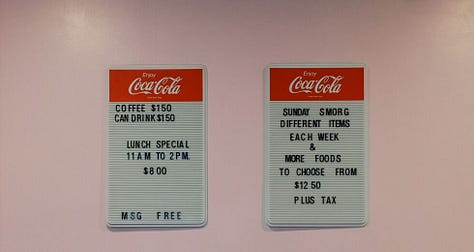

Suyin: It was always fascinating to see what was on the menu when we arrived. We saw so many variations of the menu and a wild mix of potential meals. The menus were always several pages long and had ‘Chinese’ food and ‘Canadian’ food. [The former] usually meant Cantonese dishes as the legacy of this food originated from Guangdong province, along with hybrid westernised Chinese dishes such as sweet and sour pork, chop suey or dishes made up of whatever ingredients the cooks could source and what they thought appealed to local tastes. Then the ‘Canadian’ part could be fish and chips, pizza, hamburgers, poutine, gyros, pancakes and eggs and so on.

The meals have become a blur over the course of our travels, and the most vivid memories were the way I felt when I entered each café, the emotional quality, the people I met and the way that the owners chatted with me, how the sunlight fell through the window, the warmth of the space and the encounters I had.

What languages do you speak, and how did language come into play when getting to know your subjects?

My dad was both my driver and interpreter of both language and café life. He was the conduit that allowed me to connect with many of the café owners. Many of them came from Taishan, and their dialect is so different from Cantonese (which I can get by on), that it almost feels like another language.

Yet, as soon as my dad started speaking in Taishanese, there was a visible shift in the atmosphere – they would chat about home, the villages they came from, and what it was like working in the cafés. This shared language and understanding of home really opened up the conversations.

Do you ever think about how to lens your subjects sensitively without objectifying the people or romanticising suffering?

This is a very important, challenging question. I’ve really struggled with this over the years of working on this project. For me, there is a constant tension in this storytelling about intentionality, and to try my best to honour the agency and legacy of people whose stories I am trying to tell. I felt the need to dig into the Chinese restaurant – everyone has eaten Chinese food, yet there are stereotypes about these spaces and a lack of understanding of why people came, what they were hoping for, and these really universal themes of immigration, perseverance, grit and love.

Sons & Daughters is not the story that I thought it would be. I started off thinking about the food and the history and visual documentation of the spaces, and I don’t think I was prepared for some of the stories that emerged, some of the intensity and depth. Many stories brought me to tears.

And yet, many people I spoke to seemed quite matter of fact about their stories. There wasn’t really a sadness attached to it; life could be hard work but they just got on with things. There was a practicality to it.

My dad came to Canada on a plane when he was six years old, with his nine year old cousin.

When I came over, I never gave a thought to those things. It’s just something that happened. Because my family wanted me to come so I came over and joined my father… You know these things are a spontaneous desire to improve one’s livelihood. It's not life planning or anything like that, ‘go there or go there, or here’. They just do, sort of like you say - the path of least resistance. Whatever is possible to - what they feel would improve their condition. — Steffan Looui

I’ve had many difficult conversations over the course of this project – with myself and others – about the tensions of intergenerationality. I am the first of four generations who has not worked in a Chinese restaurant.

Do you think there is an imperative to preserve the Chinese-Canadian café, even if many of the original owners do not want their future generations to work in blue collar jobs?

These cafés hold so much history. Some of them are marked as historical sites and are such important cultural markers of early Chinese immigration to Canada. It was fascinating for me to be able to step inside so many of them, especially along the West Coast, and I hope they will remain open in some way.

The early Chinese-Canadian cafés have a direct legacy from the building of the railway during the making of Canada as a nation and the restrictions that were placed upon Chinese immigration that followed. Restaurants were amongst the limited work prospects that early Chinese immigrants were allowed. These cafés were often the first and sometimes the only restaurants in towns across Canada.

Yet these cafés were also meant for generations to pass through. I am interested in seeing what happens with the next generations, where they are now, and how some have transformed their family restaurants. In the UK, A. Wong is such a beautiful example of that.

I also love the body of work that has evolved around the Chinese-Canadian café and the building of these stories upon each other. For me, in the early days of the project this was Lily Cho’s Eating Chinese, Ann Hui’s Globe & Mail articles, and Cheuk Kwan’s Chinese Restaurant series. Many of these writers had families who owned Chinese-Canadian cafés.

A question I love to ask interviewees: what does home taste like?

I love this question. It’s one I also asked café owners during my travels. There is so much family and early memory tangled up in that question. For me, it’s dumplings. We lived across the country from my grandmother and mother’s extended family. We were really isolated in small-town British Columbia, and every time we returned to Toronto, it felt like we were returning home — back to my mother’s family and the warmth and strength of that big family circle, and also back to a Chinese community. In those hot, sticky Toronto summers, I have memories of visiting her and she would call for us to come over, and told us we must sit and learn to make dumplings with her.

Did the trip challenge your own ideas about Chinese-Canadian culture?

I had this idea that Chinese people don’t really like to talk, that they might not want to open up to a stranger like me, and tell me their stories. Sometimes this was the case and I did feel some hesitancy and silence. But on even more occasions as we crossed the country, I was surprised by people’s warmth and curiosity, and a willingness to sit down and chat with me.